Managing hazardous waste can be a challenge, regardless of generator status. That’s partly because the regulatory obligations can be difficult to navigate, but also because many generators continue to struggle with the basics of determining if their wastes are hazardous in the first place.

In this first installment of our new blog series, the Guide to Hazardous Waste Management, we’ll provide a brief introduction to hazardous wastes, unpack Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) process for determining if a waste is hazardous, discuss the purpose of waste profiles, and end with some “big picture” takeaways that will help you get a handle on waste classification and pave the way for future installments of this series.

Introduction to Hazardous Wastes

Humans constantly generate waste, whether from personal, business, or industrial activities. But not all wastes are equally dangerous or come with significant regulatory obligations. EPA defines a hazardous waste as “a waste with properties that make it dangerous or capable of having a harmful effect on human health or the environment.”

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) gives EPA the authority to regulate hazardous wastes from cradle to grave, so to speak. EPA regulations cover everything from the initial generation of waste to its storage, its transportation, and its ultimate treatment, storage, and disposal at licensed facilities.

RCRA doesn’t just cover hazardous waste, either. It also establishes a framework for EPA to regulate the management of non-hazardous solid wastes, including (as we’ll see) some categories of wastes that might otherwise have been classified as hazardous were it not for special considerations that EPA applied to facilitate safe disposal or recycling. But EPA’s focus, understandably, is on reducing risks associated with hazardous waste by establishing regulatory requirements for every phase in the waste’s lifecycle.

How Do I Identify if My Wastes are Hazardous?

That’s a great question, because every other regulatory requirement for waste generators hinges upon its answer. Because of that, it’s really important we get it right—which means being familiar with EPA’s definition of hazardous waste and the process of determining if your waste(s) meet that definition.

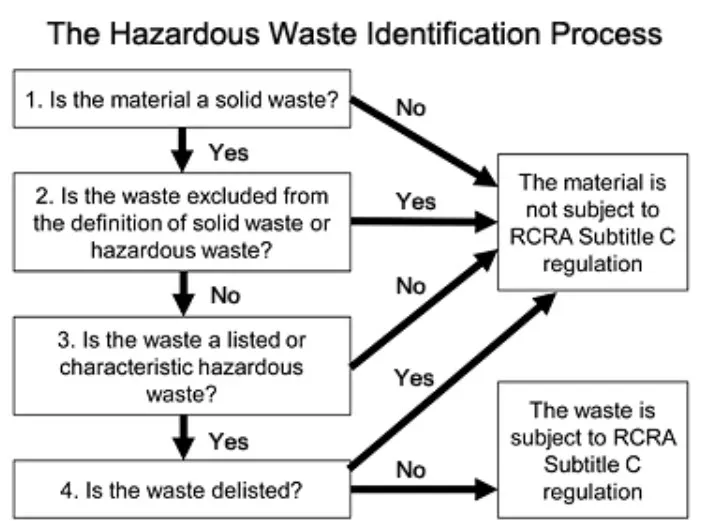

Luckily, the EPA-produced flowchart below outlines the process quite clearly.

Let’s take a close look at each step in this process.

Is the material a solid waste?

The first step in the process is to determine if our waste is a form of solid waste by RCRA’s definition. RCRA defines a solid waste as “any garbage or refuse, sludge from a wastewater treatment plant, water supply treatment plant, or air pollution control facility and other discarded material, resulting from industrial, commercial, mining, and agricultural operations, and from community activities.”

With a name like “solid waste,” you might assume that the waste must always be a literal solid, right? Not at all. The definition of a “solid waste” also includes wastes that are semi-solid, liquid or contain gaseous material.

Do any exclusions apply?

Even if a waste contains listed hazardous wastes or has hazardous characteristics, it would not be a hazardous waste if it is specifically excluded from the definition of “hazardous waste.”

Why does EPA exempt these wastes from the definition of hazardous waste? There are a number of reasons depending on the specific waste, but common ones include the objective of facilitating recycling or making safe disposal easier. A great example of the latter consideration is the specific exemption of “household hazardous wastes,” which might include wastes of common consumer products like fuels or automobile maintenance chemicals, caustic agents like drain cleaners, or solvent-based paints that may have one or more characteristics of hazardous waste. If it were too hard to dispose of these chemicals, household consumers might be tempted to dispose of them in very environmentally unfriendly ways. That’s why many municipalities offer household hazardous waste drop-off locations, or otherwise make it easy for ordinary community homeowners to dispose of dangerous waste chemicals.

The table below lists all of the solid wastes that EPA excludes from classification as hazardous waste, along with the exact regulatory citation associated with the exclusion. For more information about each exclusion, consult the regulatory citation indicated.

| Solids Wastes That are Not Hazardous Wastes | Regulatory Citation |

| Household Hazardous Wastes | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(1) |

| Agricultural Waste | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(2) |

| Mining Overburden | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(3) |

| Fossil Fuel Combustion Waste | 40 CFR 261.3(b)(4) |

| Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Wastes | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(5) |

| Trivalent Chromium Wastes | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(6) |

| Mining and Mineral Processing Wastes | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(7) |

| Cement Kiln Dust | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(8) |

| Arsenical-Treated Wood | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(9) |

| Petroleum Contaminated Media & Debris from Underground Storage Tanks | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(10) |

| Injected Groundwater | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(11) |

| Spent Chlorofluorocarbon Refrigerants | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(12) |

| Used Oil Filters | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(13) |

| Used Oil Distillation Bottoms | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(14) |

| Landfill Leachate or Gas Condensate Derived from Certain Listed Wastes | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(15) |

| Project XL Pilot Project Exclusions | 40 CFR 261.4(b)(17) and (18) |

Is the material a listed hazardous waste?

“Listed wastes” are wastes generated from specific processes. A waste is automatically hazardous if it is specifically listed on one of the four EPA lists below:

- The F-list, found at 40 CFR 261.31, contains wastes from common manufacturing and industrial processes, including spent solvent wastes, electroplating and other metal finishing wastes, petroleum refinery wastewater treatment sludge, dioxin-bearing wastes, wood preserving wastes, multisource leachate, and wastes from chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons production.

- The K-list contains source-specific wastes from 13 specific industry sectors. A waste would be defined as a K-list waste if meets the detailed description of the waste as provided in 40 CFR 261.32. A sampling of those sectors includes wood preservation, pesticides manufacturing, petroleum refining, iron and steel processing, and primary aluminum production.

- The P and U lists have some similarities, in that both pertain to pure and commercial grade formulations of commercial products that are being discarded unused. That last part is important, because if the material contains used chemical product, it would not be a P or U listed waste. The P-list identifies acute hazardous wastes from discarded commercial products and is found while the U-list identifies specific non-acute wastes. You can find both lists at 40 CFR 261.33.

For convenience, you can also search for specific P and U listed wastes by using the search bar EPA provides at this site.

Is the material hazardous based on characteristics?

If the waste is not a listed hazardous waste, it might still be a hazardous waste based on its characteristics. A “characteristic” is a property that, when present, indicates that the waste poses a significant enough threat to merit regulation as a hazardous waste.

The four hazardous waste characteristics to watch for are:

Ignitability: Ignitable wastes include liquids with flash points below 60 °C/140 °F, non-liquids that cause fire through specific conditions, ignitable compressed gases and oxidizers. EPA has assigned D001 as the waste code for ignitable hazardous wastes. Many common solvents, in waste form, would be characteristic D001 wastes based on ignitability. If you have a solvent product that, according to its safety data sheet (SDS) arrives as supplied with a flash point below 140 °F, there’s a pretty good chance that the waste version of the product will be ignitable, unless it undergoes some form of chemical change or dilution while it’s being used. That’s why many generators just classify based on the flash point of the product as supplied. But if you’re not sure if the waste would be ignitable, you’d need to have a sample of it analyzed according to approved EPA test methods.

Corrosivity: Wastes meet the parameters for the corrosive characteristic if they have a pH of less than or equal to 2, or a pH greater than or equal to 12.5. If you recall your chemistry classes, a liquid is neutral at a pH of 7, acidic if its pH is below 7, and basic/alkali if above 7. Therefore, liquids with pHs in the range defined by EPA as corrosive would be strongly acidic or strongly basic. The former category would include wastes of strong acids like sulfuric acid or muriatic acid, and the latter would include wastes containing strong bases such as sodium hydroxide, often sold commercially as “caustic soda” or “lye.” EPA also considers wastes corrosive if they have the ability to corrode steel in a specific test protocol. EPA’s waste code for corrosive wastes is D002.

Reactivity: Wastes with the characteristic of reactivity may be unstable under normal conditions, may react with water, may give off toxic gases and may be capable of detonation or explosion under normal conditions or when heated. This characteristic is a little different from the other two we’ve already seen because it is not defined based on specific, numerically measured properties like pH or temperature of flash point, and there is no EPA established test method for reactivity. But you can learn more about how to determine this characteristic by reading this Reactivity Characteristic Background Document. Keep in mind, though, that chemical products with SDSs that identify hazards such as oxidation or water reactivity would likely have reactive characteristics in waste form. A waste solution of lithium aluminum hydride, which is extremely water-reactive and can even cause fire or explosions if it comes in contact with water, would be a reactive hazardous waste. EPA’s waste code for reactive wastes is D003.

Toxicity: Wastes have the characteristic of toxicity if they have the ability to leach into groundwater, where they can potentially impact human health. Generators need to determine the toxicity of their waste using the Toxic Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP). In this case, there is not just one EPA waste code but many, comprising codes D004 through D043 depending on the contaminant and its associated TCLP concentration.

Is the waste delisted?

Suppose you have a listed hazardous waste, as I just defined. As a generator of the waste, you have an option of petitioning EPA to delist your specific waste based on evidence that it does not contain the dangerous properties possessed by other wastes on that EPA list.

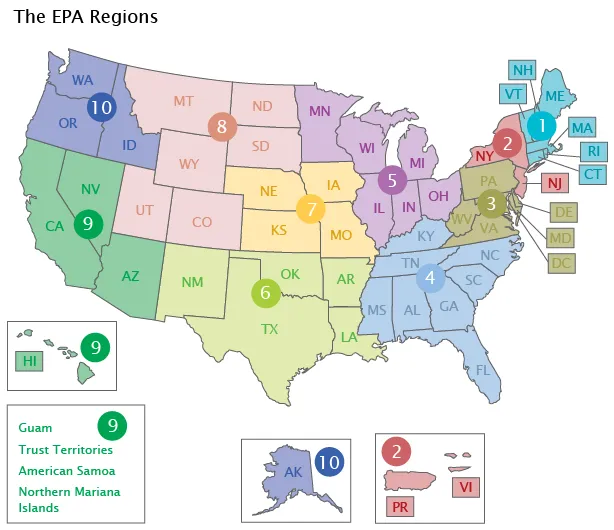

This works like a kind of petition or appeal process. Generators who believe their listed waste should be delisted would prepare their case, usually consisting of information about the chemical composition of the waste, such as laboratory analytical results. The delisting process can vary depending on whether federal EPA regional office or state EPA would have authority, so the generator would need to figure that out first, and then follow the correct process. EPA’s image below shows which EPA regions correspond to different areas of the country.

You would need to continue managing the waste as hazardous until or unless you learn that the appropriate office has approved the delisting. How likely are you to succeed in getting your waste delisted? That’s going to depend on the specific details about your waste, but you can review a list of facilities that have successfully petitioned to have wastes delisted in Appendix IX of 40 CFR part 261.

Profile Your Wastes

Once you’ve characterized your wastes as hazardous or not, you’ll need to complete waste profiles for each waste. A waste profile is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a form describing a specific waste, including the process that generates it, whether the waste is hazardous, and if so, the specific EPA waste codes that apply. The profile provides the required treatment, storage, and disposal facility (TSDF) with the information to safety handle and dispose of or treat the waste and comply with applicable regulations. Therefore, we can see that the accuracy of the waste profile depends on the hazardous waste determination itself being accurate, and that there’s a lot that can go wrong if it’s not.

Keep in mind that some TSDFs have pre-prepared forms that they send to their customers to complete. Most disposal facilities will not accept wastes without a profile accompanying the manifest. In fact, some require the waste profile in advance so that they can determine if they will even be able to accept the waste, and what they will need to do to be prepared to receive it. These forms will often assign the profile a specific number, which will be included on hazardous waste manifests once the waste is shipped to that TSDF.

Once you have your profiles, you’re going to need to make sure they’re organized and accessible. These documents show that you’ve properly characterized your waste and includes the information that you relied on for that determination. These are important to have readily on hand in the event of a hazardous waste compliance inspection and will play a central role throughout your waste management programs, as we’ll see in subsequent installments of this series.

The Big Picture

We can see that there’s much to consider in the process of determining if your wastes are hazardous. Let’s boil it down a little to a few high-level takeaways:

- Understand your processes: This is important for a couple of reasons. You need to know which processes generate waste to know what specific wastes you even generate. And you’ll also need to know if any of these processes correspond to EPA lists F,K,P, and U as described earlier, which would result in your waste being a listed hazardous waste.

- Understand your chemicals: This is crucial for determining if your wastes are hazardous based on characteristics, since knowing the hazards and physical properties of chemicals in your inventory often provides a good indications about the corresponding hazards and properties of the wastes containing that chemical. For example, if we use a caustic cleaning product that has a pH greater than or equal to 12.5 as supplied, there’s a potential that the spent product would have the same pH range and if so, would be hazardous based on the corrosive characteristic. You’re a lot more likely to have good visibility of these chemical properties with SDS/chemical management software that enables you and your employees to access SDS easily, especially if it includes ingredient indexing capabilities to help you identify components within chemical products that might cause the waste product to be hazardous.

- Manage your waste profiles: You’re going to need fast access to your waste profiles to document compliance, manage your waste shipment responsibilities and plan future waste minimization initiatives. Make sure you have a system that enables fast access to your profiles at any time.

The truth is, we’ve only just scratched the surface so far. We haven’t even talked yet about how to determine your hazardous waste generator status, identify and maintain your regulatory obligations based on your status, and properly ship your wastes. But be sure to check this space for future installments of this blog series, in which we’ll cover all of those topics and more!

Let VelocityEHS Help!

Looking for support getting a handle on hazardous waste management? Waste Management from VelocityEHS can help. We can help you assign EPA waste codes to your hazardous wastes and maintain all of your waste profiles in a single, easily accessible system, so you can document your waste classifications. And we can help with all other facets of waste management, including tracking of hazardous waste manifests, and generation of EPA-required hazardous waste reports (HWRs) as well as reports to support internal waste minimization efforts.

As always, please feel free to contact us anytime more information.