If you’re looking for information about how upcoming changes to OSHA’s HazCom Standard will affect your business and safety management practices, or about the GHS in general, you’ve come to the right place. As you explore this Resource Center, you’ll find the details you need about the context and history of the HazCom Standard, the major changes coming because of OSHA’s 2024 final rule, the compliance timeline, and major takeaways about how to prepare. If you’re looking for details about the history of GHS and its global adoption status in different areas, you’ll find that here, too.

Click on the links below to start exploring and be sure to check back here periodically for updates from OSHA about the HazCom changes, or about news regarding GHS adoption around the world.

Want to see how the VelocityEHS Chemical Management Solution can simplify GHS/HazCom compliance and workplace chemical management? Check out our solutions page to learn more or schedule a demo.

GHS Explained

Discover what the GHS is, why it was developed, and how it is used worldwide for hazard communication.

History of GHS

GHS dates back to the 1992 United Nations Conference, where the need was first recognized.

Background of OSHA’s Changes

Learn about the background of OSHA’s 2024 final rule, including the history and purpose of the HazCom Standard.

Reviewing the Main Changes

Get a comprehensive overview of the major changes to the HazCom due to the 2024 final rule.

Compliance Transition Timeline

Learn the compliance timeline for OSHA’s 2024 final rule for different parties throughout the chemical supply chain.

Glossary of Terms

Visit our glossary page to better understand common technical terminology used in GHS.

Links to Useful Information

Explore useful GHS information from various organizations such as the UN, OSHA, EPA, and more.

GHS Resources

Explore GHS blog articles, compliance checklists, webinars, guides, and ebooks.

GHS Explained

What is GHS?

GHS stands for the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals.

Developed by the United Nations, the premise of the GHS is that existing chemical classification and labelling systems should be harmonized in order to develop a single, globally harmonized system to address classification of chemicals, labels and safety data sheets.

Why have the GHS?

Given the large number of hazardous chemicals in the world, the ability of one agency to effectively regulate them all is impractical if not impossible. In essence, each country or organization is on its own.

Many countries and organizations have established laws and regulations requiring information to be prepared and transmitted through labels and/or safety data sheets to those people using or handling hazardous chemicals.

The Background of OSHA’s HazCom Changes

Reviewing the Major HazCom Changes

OSHA published their HazCom final rule on May 20, 2024, finally ending years of anticipation by stakeholders. Keep reading to learn some of the major changes to HazCom due to the final rule and check back often for updates.

The Compliance

Transition Timeline

OSHA has extended the timeline for compliance with the final rule, compared to the timeline originally proposed in the NPRM. The proposed phased-in compliance timeline had been 1 year for manufacturers of substances and 2 years for manufacturers of mixtures. Between the effective date and the respective compliance dates for substances and mixtures, manufacturers of chemicals can comply with either the previous version of the HazCom Standard or the revised Standard when classifying their chemicals, authoring SDSs and labeling their shipped containers.

Based on stakeholder feedback, OSHA has lengthened the timeline in the final rule to 18 months for manufacturers of substances and 36 months for manufacturers of mixtures, as measured from the final rule’s effective date of July 19, 2024. Employers at workplaces using chemical products affected by the final rule would have six months from the manufacturer deadlines for substances and mixtures, respectively, to make any changes necessary to workplace hazard communication practices (e.g., workplace labels, written HazCom plan, and worker training) based on updated chemical hazard information provided by their suppliers.

Big Takeaways on HazCom Changes

OSHA’s 2024 HazCom final rule represents the first significant update to the HazCom Standard since OSHA aligned the standard with GHS Revision 3 in 2012.

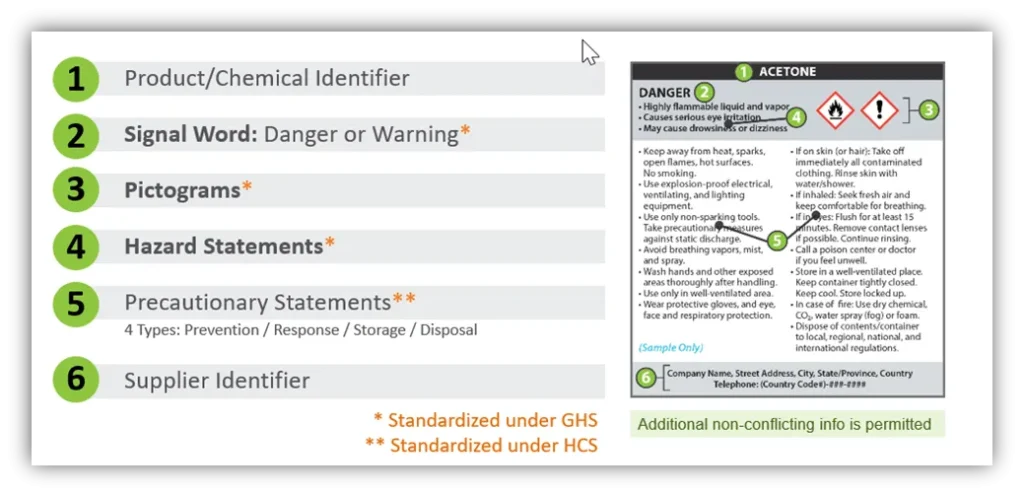

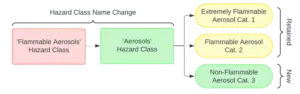

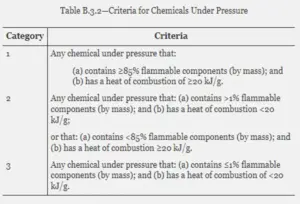

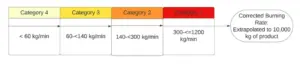

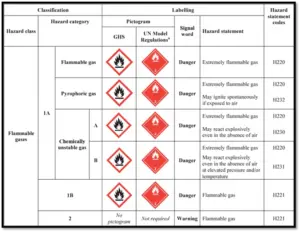

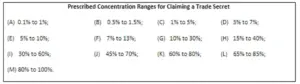

With modifications to existing hazard classifications and labelling elements and the addition of new hazard classes, hazardous chemical manufacturers, importers and distributors in the US will need to re-evaluate the hazards of the products they sell or import into the country to ensure product hazards are classified and labelled according to revised HazCom criteria. This is particularly true for chemicals in the hazard classes of flammable gases, aerosols, chemicals under pressure and desensitized explosives, because OSHA’s changes to hazard classifications directly affect those products.

Therefore, many SDSs and shipped container labels for chemicals impacted by the proposed changes will need to be re-authored to reflect changes in chemical hazard classification or mandatory labelling information and ensure compliance with updated requirements. Specific industry sectors identified by OSHA as affected by these changes include chemical manufacturing, oil and gas extraction, and plastics and rubber products manufacturing will be more significantly affected by these classification changes. All chemical manufacturers will also need to prepare for the new shipped container label allowances and requirements for small and very small containers. In the final rule, OSHA estimates that 94.4% of SDSs and 64% of labels (non-small/very small) will need revision.

However, all users of hazardous chemicals throughout the supply chain will be impacted by these changes, too. Employers at facilities where these chemicals are used and stored will need to be aware of the changes to classifications and associated information, such as hazard pictograms, hazard statements and precautionary statements, and use the updated information on workplace container labels. They may also need to update their written HazCom plan to reflect the new information, and update the HazCom training they provide to employees who work with hazardous chemicals.

The preparation starts with understanding your chemical inventory, and knowing whether you have chemical products affected by the coming changes. You’ll also need simple and time-efficient ways to manage your SDS library as new documents arrive, and to provide your workforce with barrier-free access to SDSs during their workshift.

No matter where you are in the chemical supply chain, VelocityEHS can help you. Chemical and SDS management capabilities in our Safety Solution, part of our Accelerate Platform®, can help you maintain an up-to-date chemical inventory and SDS library, and provide access to all of your SDSs from anywhere using a mobile device. We can also help you quickly print workplace container labels containing hazard communication information from your current SDSs. And if you’re a chemical manufacturer, importer, or decide to create your own SDSs and labels, the authoring and regulatory consulting services provided by our in-house experts will help you create SDSs and shipped labels that reflect the latest HazCom changes before the compliance deadline.

Contact us today to learn more about how we can help you be safer and more sustainable.

Links to Useful Information

United Nations

OSHA

- OSHA Questions and Answers on HazCom 2024

- OSHA HazCom 2024 Fact Sheet

- OSHA Fact Card on Safety Data Sheets (pdf)

- OSHA Fact Card on Labels (pdf)

- OSHA Fact Card on Pictograms(pdf)

- OSHA HCS FAQs

- Compliance Deadlines

- Revised HCS Appendix C (Labels)

- Revised HCS Appendix D (Safety Data Sheets)

EPA

US DOT

US Consumer Product Safety Commission

Canada

- Health Canada: GHS

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOSH) WHMIS Page

- Amendments to Hazardous Products Regulations (2023)

Australia

New Zealand

EU

- UNECE About GHS

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) Understanding CLP Page

- 2023 Delegated Regulation Updating CLP

- REACH regulation

- European Commission on Enterprise and Industry

- Health and Safety Authority – Ireland

- OECD (pdf)

United Nations (UN)

Looking for additional guidance?

A Deeper Dive into OSHA’s Final Rule Updating the HazCom Standard

eBook

Chemical Management

This eBook will help you understand the HazCom final rule and prepare to meet updated requirements.

OSHA’s HazCom Standard: Readiness Checklist for The Final Rule Aligning with GHS Revision 7

Guide

Safety

This checklist will help you understand some of the most important tasks you need to complete to ensure compliance with OSHA’s updated HazCom Standard.

ARCHIVED CEU Webinar: OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule Panel Discussion

On Demand Webinar

Safety

Attend this one-hour webinar to earn CEUs! Join VelocityEHS chemical safety and compliance experts for a panel discussion regarding OSHA’s HazCom Standard.

ARCHIVED CEU Webinar: OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule

On Demand Webinar

Chemical Management

Learn how to master the 5 key areas of HazCom compliance, take a deep dive into GHS Revision 7 updates, and get actionable steps for ensuring compliance.

OSHA Inspection Preparation Checklist

eBook

EHS, Safety

This OSHA Inspection Preparation Checklist is intended to help you navigate the OSHA inspection process, and minimize your compliance risk.

ARCHIVED GHS/HazCom: Maintaining Compliance & Preparing the Future

On Demand Webinar

Safety

This webinar explains the key GHS changes to HazCom, addresses common questions and reviews recent regulatory activity.

Five Steps to HazCom Compliance Infographic

Infographic

Safety

Our infographic covers every step you need to take to keep your workers safe and your facility compliant.

National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) Reporting: Managing Compliance

On Demand Webinar

Safety

Mandatory NPRI reports are due by June 1 of each year if you are subject to reporting requirements. Are you in compliance?

A Closer Look at OSHA’s Final Rule Updating the HazCom Standard

Safety

Here’s a closer look at OSHA’s final rule updating HazCom, and how the changes impact your business and your chemical management practices.

Ready to see VelocityEHS in action?

Request a demo today to see how we help organizations like yours gain control of their EHS & ESG strategy and empower global teams for success.

Partner with the most trusted name in the industry

Stress less and achieve more with VelocityEHS at your side. Our products and services are among the most recognized by industry associations and professionals for overall excellence and ease of use.