By Phil Molé, MPH

OSHA published its long-awaited final rule updating requirements in its Hazard Communication (HazCom) Standard. The publication of OSHA’s final rule ended months of waiting and uncertainty by manufacturers and users of hazardous chemicals and aligns HazCom with updated versions of the UN’s Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), mostly Revision 7, but includes select elements of Revision 8. Users of hazardous chemicals throughout the supply chain, from chemical manufacturers or importers to distributors to end users, need to understand the HazCom final rule and start preparing to meet updated requirements.

This blog covers what you need to know about OSHA’s final rule, including its background, its major changes to the HazCom Standard, and most importantly, how those changes will affect you.

What is the Background of OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule?

At a high level, the major changes associated with OSHA’s final rule include:

| Change | Details |

| Updated hazard classes and classification criteria | Revised hazard classifications for aerosols, desensitized explosives, flammable gases, and chemicals under pressure (a new category within the aerosols class). |

| Updated labeling allowances and requirements for “small” and “very small” containers | Allowance for manufacturers of chemicals in small containers (100 mL or less) to use abbreviated shipped container label information on immediate container, and for manufacturers of very small containers (3 mL of less) to put only the product identifier on the immediate container if a label would interfere with use of the container. In both cases the outer packaging must have full shipped container label information, and the label must tell users to keep the small or very small containers in the outer packaging when not in use. |

| Labeling provisions for containers “released for shipment” | Allowance for manufacturers, importers or distributors who become aware of new significant hazard information to not need to relabel chemical products already released for shipment (bundled, palletized, etc.) |

| Updated criteria to consider when classifying a chemical | Clarified and updated requirements for chemical manufacturers to consider intrinsic properties including hazards due to known or anticipated downstream uses when classifying their products and include these details in SDS Section 2. |

| Updated information requirements for SDSs | Several changes to information required on SDSs, including addition of “particle characteristics” to Section 9, and clarification of the need for Section 1 to contain domestic contact information, and updated instructions on information for chemical manufacturers to include in Section 2. |

| Updated and expanded classification methods for some chemicals, and updated classification instructions | Allowance of new classification methods for some chemicals including oxidizing solids, while updating or clarifying instructions for several other categories. |

What’s Changing Because of OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule?

OSHA published its HazCom final rule in the Federal Register on May 20, 2024.

Here’s a closer look at the changes brought by OSHA’s final rule:

Revised Classification Criteria

Flammable Gases

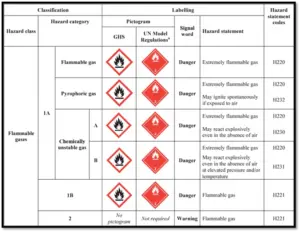

OSHA’s final rule subdivides Category 1 of this hazard class into two subcategories (1A and 1B), requiring pyrophoric gases and chemically unstable gases to be classified as Category 1A. OSHA maintains that these changes will provide more detailed information about flammable gas hazards and align with GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060). Under HazCom2012, products classified as Flammable Gas Category 1 could have a wide range of flammability properties, so this update to subdivide category 1 will allow more specific and concise hazard communication information relative to a flammable gas’s intrinsic properties.

The tables below show OSHA’s updated flammable gas categories and associated hazard communication elements:

OSHA proposed these changes in their 2021 HazCom Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), intending to give downstream users a better understanding of the severity of hazards associated with flammable gases. Specifically, downstream users could use this information to take appropriate precautions under all conditions (i.e. transport, handling and use) or determine if an available substitute chemical is less hazardous. Furthermore, OSHA noted that the proposed bifurcation (splitting flammable gases Category 1 into Category 1A and 1B) would not alter transportation requirements for flammable gases because all flammable gases categorized as either 1A or 1B would still count as Category 1 flammable gases for the transportation classification and communication scheme.

OSHA’s classification of pyrophoric gases in the final rule recognizes newer strategies for protecting workers from the hazards of these chemicals. When OSHA first aligned the HazCom Standard with GHS Revision 3 in 2012, the GHS did not yet classify pyrophoric gases. To ensure that the 2012 HazCom update would communicate the hazards of pyrophoric gases and not reduce worker protections, OSHA added pyrophoric gases under the definition of a “hazardous chemical” in paragraph (c) of the HazCom Standard. After the 2012 final rule, UNSCEGHS updated the criteria for flammable gases in GHS Rev. 6 to include pyrophoric gases. GHS Rev. 7, which OSHA is mostly aligning with via the 2024 final rule, instructs chemical manufacturers to classify pyrophoric gases and chemically unstable gases as Category 1A flammable gases, and OSHA is adopting that classification via the final rule.

Desensitized Explosives

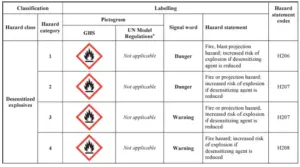

OSHA’s final rule is following GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060) by adding a new physical hazard class for desensitized explosives. There will be 4 categories (1,2,3, and 4) within this new hazard class in new Appendix B.17.

Desensitized explosives are explosive chemicals treated to stabilize the chemical or reduce or suppress explosive properties. To be classified as a desensitized explosive, a chemical must be a solid or liquid, must remain homogenous with its desensitizing/stabilizing agent, and cannot also be classified as an explosive, flammable liquid, or flammable solid.

Desensitized explosives pose explosive-equivalent hazards in the workplace when the stabilizer is removed or inadvertently lost, either as part of the normal work process or when the chemical is stored. Therefore, it is urgent that chemical manufacturers identify and appropriately communicate hazards, including the importance of the stabilizer.

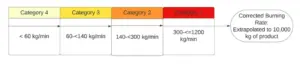

The chart below shows the four categories of desensitized explosives as adopted by the final rule. The “burning rate” in the chart refers to its combustion rate as determined by testing the product in packaging as stored and used. Note that the upper range of Category 1 is 1200 kg/min. This makes sense considering the concept of desensitized explosives, since there needs to be an upper limit on the burn rate of a chemical for it to be able to be stabilized. In the chart, products with a burn rate greater than 1200 kg/min would be explosives.

The 2012 HazCom Standard (which OSHA aligned with GHS Rev. 3) acknowledged that these chemicals would be explosives if the wetting agents weren’t used, including them in Appendix C, C.4.14 with the precautionary statement “keep wetted with” followed by the name of the appropriate wetting agent. Still, the limitation of this method was that desensitized explosives were covered by the ‘explosives’ hazard class under HazCom 2012, and hazard information such as the precautionary statement, pictogram, hazard statement and signal word required under C.4.14 primarily target more conventional explosives, for example the exploding bomb pictogram was present for desensitized explosives under HazCom2012. Many stakeholders recognized that ineffective or inaccurate communication carried serous risks of danger, since if users did not understand and apply the precautions to keep desensitized explosives wetted, the materials could become explosive, especially after long-term storage.

To better ensure that downstream users would receive and understand necessary handling and storage precautions, the UN Sub-Committee of Experts on GHS (UNSCEGHS) determined that desensitized explosives merited a separate hazard class, which they provided in GHS Revision 7. The desensitized explosives class is associated with a flame pictogram rather than the exploding bomb pictogram used for other explosives. The final rule adds the desensitized explosives hazard class to the HazCom Standard as Appendix B.17, and the image below shows the hazard communication elements associated with the four desensitized explosive categories:

Hazard statements associated with each of the four categories highlight the importance of keeping the desensitized explosive stabilized, stating, “increased risk of explosion if desensitizing agent is reduced.” The final rule also requires precautionary statements to “keep wetted with” the appropriate agents for the specific chemical. Manufacturers must include specific information in key sections of the SDSs, such as details about shelf life and ways to verify desensitization in Section 10.

OSHA’s final rule states that even though “desensitized explosives” is a new hazard class, the explosion hazards are well-known, and employers should already cover them in current hazard communication training. OSHA maintains that the new classification will further improve workplace safety.

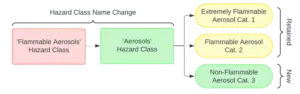

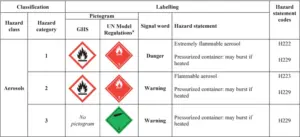

Aerosols

OSHA’s final rule is following GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060) by renaming the existing Flammable Aerosols hazard class “Aerosols” and expanding Appendix B.3 to include non-flammable aerosols, while retaining flammable aerosols. Non-flammable aerosols will now be under a newly created Category 3, while flammable aerosols will continue to be under Category 1 or Category 2.

In its 2021 NPRM, OSHA maintained that most aerosols were classified as gases under pressure by GHS Rev. 3 (and accordingly under HazCom 2012) because of the design criteria of the aerosols (ERG, 2015, Document ID 0163) under DOT regulations. Since HazCom 2012 went into effect, OSHA has learned that their classification did not adequately represent the full spectrum of varying aerosol hazards, because aerosol containers have different characteristics including failure mechanisms. Accordingly, OSHA proposed to classify flammable aerosols in existing Categories 1 and 2 and bear the flame pictogram, but to classify non-flammable aerosols in a new Category 3 with no pictogram. The diagram below shows the new categories and their associated labeling elements:

OSHA’s final rule adopts the revisions to the aerosols hazard class as proposed. It should be noted that in their 2021 NPRM, OSHA had also solicited stakeholder feedback on whether to adopt classification criteria for aerosols from text in a table in GHS Rev. 8, specifically Table 2.3.1, rather than using decision logic for classification. However, due to NIOSH pointing out inconsistencies in Table 2.3.1, OSHA indicated that they would not adopt the GHS 8 table at this time and would work with the UN subcommittee to ensure that subsequent editions of the GHS address inconsistencies and improve worker protections.

Aerosol manufacturers can expect the final rule’s classification changes to significantly impact the authoring of SDSs for affected products.

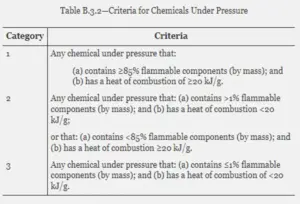

Chemicals Under Pressure

OSHA has adopted a new hazard category, Chemicals Under Pressure, within the aerosols class following classification criteria in GHS Revision 8. These revised classifications also change some associated hazard information, including hazard pictograms and hazard and precautionary statements.

The term “chemicals under pressure” refers to liquids or solids in a receptacle (other than an aerosol dispenser) pressurized with a gas at a gauge pressure of >=200 kPa (29 psi) at 20°C / 68°F. A product classified as a chemical under pressure cannot also be classified as an aerosol, a gas under pressure, or a flammable gas, liquid, or solid. In general, chemicals under pressure typically contain 50% or more by mass of liquids or solids whereas mixtures containing more than 50% gases are typically considered as gases under pressure.

In finalizing the chemicals under pressure hazard classification, OSHA has included all three categories as defined in Table 2.3.3 in Rev. 8 and largely included the hazard communication elements in Table 2.3.4 in Rev. 8 (Document ID 0065, p. 62) in Appendix C.16. The table below shows the chemical under pressure categories and associated classification criteria adopted in the final rule.

OSHA’s final rule largely implemented GHS Revision 8 labeling elements for Chemicals Under Pressure; however, OSHA did modify the Hazard Statements relative to GHS Revision 8 – particularly by using the word “burst” instead of “explode” for categories 1 and 2, and by using the same Hazard Statement for a Category 3 Chemical Under Pressure as is required by the Aerosols Category 3 classification.

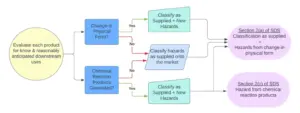

Classification Based on “Intrinsic Properties” and Known Downstream Uses

OSHA’s final rule states that, “hazard classification must include hazards associated with the chemical’s intrinsic properties including: (i) a change in the chemical’s physical form and; (ii) chemical reaction products associated with known or reasonably anticipated uses or applications.” The final rule clarifies that hazards from a chemical reaction (the actual GHS-based classifications) belong in Section 2(c) of the SDS, and hazards from changes in intrinsic and physical form belong in 2(a).

Stakeholders during the public comment period possibly expressed more concerns about this provision of the NPRM than any other, especially because the NPRM’s original text referencing “normal conditions of use” and “foreseeable emergencies” seemed too broad. Some chemical manufacturers worried that they’d need to factor in every possible downstream use and scenario when classifying a chemical, and that was effectively impossible. OSHA’s updated text in the final rule is an attempt to delineate the narrower expectations for manufacturers to classify chemicals only based on “known or reasonably anticipated uses.”

OSHA provides the following useful summary in the text of the final rule:

“In conclusion, OSHA agrees with commenters that it would not be possible for every manufacturer, importer, and distributor to be aware of every single use or application of its products, and the agency is not requiring these entities to do the kind of intensive investigations that many of the commenters described as infeasible. Additionally, regulated parties will not immediately be aware of all uses when new products are developed or when there are trade secret issues with downstream users. Similarly, OSHA would not expect a manufacturer to know every use of feedstocks (raw materials used to make other chemical products), starting materials or commodity chemicals, solvents, reactants, or chemical intermediates where there could be thousands of uses or the substances are used in downstream manufacturing to produce new chemical products. However, the agency concludes that manufacturers must make a good faith effort to provide downstream users with sufficient information about hazards associated with known or reasonably anticipated uses of the chemical in question. As discussed above, OSHA is finalizing language to make this clear, and to tie the classification obligation to either the manufacturer, importer, or distributor’s own knowledge or facts that the manufacturer or importer can reasonably be expected to know.”

The diagram below provides some takeaways on how chemical manufacturers can move forward with classifying their chemicals under the revised guidelines.

New Provisions for “Small” and “Very Small Containers

Allowances for “Small Containers”

OSHA’s final rule incorporates guidance previously provided by OSHA for labeling “small containers” into the text of the Standard, defining a small container as 100 mL or less in volume. Paragraph (f)(12) in the revised standard, addressing labeling of small containers, specifies that chemical manufacturers, importers and distributors can include less information on the shipped label when they can demonstrate that it is not feasible to use pull-out labels, fold-back labels or tags to provide the full label information as required by paragraph (f)(1).

Allowances for “Very Small Containers”

OSHA’s final rule allows chemical manufacturers, distributors, or importers to provide only a product identifier on “very small containers” (3 ml or less) if they can demonstrate that a label would interfere with the normal use of the container, although they’d still need to include the full shipped container label information on the outer packaging.

Requirements for Both Small and Very Small Containers

Manufacturers of both small and very small containers must include the following information on the label of the immediate outer package:

- Full shipped container label information for each hazardous chemical, and

- A statement that the small container(s) must be stored in the immediate outer package when not in use.

OSHA established these requirements to balance out the allowances for chemical manufacturers to use less information on the immediate chemical container, to ensure that end users can easily access the full range of information normally present on the shipped container label.

OSHA essentially finalized these guidelines for small and very small containers as proposed in the 2021 NPRM. Stakeholders during the public comment period appreciated being able to include only the product identifier on very small containers but argued that OSHA shouldn’t require chemical manufacturers to demonstrate that a label would interfere with use of the container to be able to use the allowance. OSHA disagreed with this feedback, stating that “requiring a showing of infeasibility is appropriate” because the default approach needs to be “ensuring that, whenever possible, workers have the full label information on the immediate container to ensure safe use at all times.” Based on this analysis, OSHA retained the requirement for manufacturers to demonstrate that a shipped label would interfere with the use of the container.

New Labeling Provisions for “Containers Released for Shipment”

OSHA’s final rule states that manufacturers, distributors, or importers that become aware of new significant hazard information would not need to relabel chemical products already released for shipment, as previously required.

Over the years, many stakeholders informed OSHA about the difficulty, and danger, of accessing shipped containers that had already been “released for shipment,” meaning they’d been bound together or secured to pallets. Suppose a manufacturer learns of new hazard information about a chemical that’s already been bundled up for shipment into commerce. Employees would need to potentially cut apart binding, climb up onto palletized shipments, and physically struggle to access the shipped labels on individual containers. These efforts could lead to many bad outcomes, including employee injuries or spills of hazardous chemicals. That’s why OSHA proposed to eliminate the requirement for chemical manufacturers to relabel packages released for shipment in their 2021 NPRM. Stakeholders supported this regulatory change, so OSHA made it official in the final rule.

However, OSHA has not finalized its modified requirements exactly as written in the NPRM, and most notably is not requiring a “released for shipment” date on the label. OSHA had originally maintained that requiring chemical manufacturers to provide the date a chemical is released for shipment on the label would allow manufacturers and distributors to determine their obligations more easily under paragraph (f)(11) when new hazard information becomes available. Stakeholders objected, citing practical concerns about lack of space for a “released for shipment” date on the label, costs of updating printed label stock, or how to determine the date to use. Based on this feedback, OSHA dropped the “released for shipment date” label requirement from the final rule.

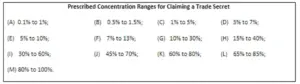

Concentration Ranges and Confidential Business Information (CBI)

In the 2021 NPRM, OSHA proposed several changes to paragraph (i) of HazCom, describing the conditions under which a chemical manufacturer, importer, or employer may withhold the specific chemical identity (e.g., chemical name), other specific identification of a hazardous chemical, or the exact percentage (concentration) of the substance in a mixture, from the SDS as a trade secret, or CBI. OSHA proposed to allow manufacturers, importers, and employers to withhold a chemical’s concentration range as a trade secret, which had not previously been permitted, and to clarify that it is Section 3 of the SDS from which trade secret information may be withheld.

After considering all stakeholder feedback, OSHA finalized its proposed CBI changes mostly as proposed but added a new paragraph (i)(1)(vi) allowing the use of narrower ranges than those prescribed in (i)(1)(iv) and (i)(1)(v). The range must be fully within the bounds of a prescribed range listed in (i)(1)(iv) or fully within the bounds of a combination of ranges allowed by (i)(1)(v).

The table below shows the prescribed concentration ranges OSHA is adopting:

Information Requirements for SDSs

OSHA has updated information requirements for SDSs, including addition of “particle characteristics” for solid products in Section 9 of SDSs.

The 2021 NPRM proposed that only manufacturers of solids would need to include “particle characteristics” information such as particle size (median and range) and, if available and appropriate, further properties such as size distribution (range), shape, aspect ratio, and specific surface area in the SDS. OSHA explained that they were trying to better align with GHS Revision 7, which includes an updated list of physical properties for chemical manufacturers to include in Section 9, and that characteristics such as particle size distribution were important determinants of hazardous properties, since particles less than 100 microns in size carried greater exposure risks, especially through inhalation.

The final rule adopts the “particle characteristics” requirement essentially as proposed in the NPRM. OSHA explained that the Standard does not require chemical manufacturers to conduct testing to determine particle characteristics, and that chemical manufacturers would not need to present particle characteristic information in a specific order.

OSHA’s final rule makes several other slight revisions to Section 9 requirements. For example, OSHA has added a parenthesis stating, “includes evaporation rate” in Section 9 (o), Vapor pressure.

Other minor changes include the term “viscosity” replacing “kinematic viscosity” and “physical state” replacing “appearance (physical state, color, etc.)”

Remember that OSHA has also finalized revised requirements for including hazards due to known or reasonably anticipated downstream uses in Section 2, and has stated that under some circumstances, importers may need to author new SDSs for products from foreign suppliers that didn’t come with SDSs containing domestic supplier contact information. Altogether, these changes will affect SDSs for many products.

Labeling for Bulk Shipments

OSHA’s final rule codifies an allowance for bulk shipments originally provided via a 2016 joint memorandum, clarifying that labels required under OSHA’s HazCom Standard and by Department of Transportation (DOT) Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) can appear on the same container.

OSHA and DOT originally issued the 2016 joint memorandum because while both agencies have policies that containers should not be labeled with any labels required by regulatory agencies other than their own, they were aware of situations in which a manufacturer or distributor might want to put both kinds of labels on the same package. For example, a tanker truck or railcar that’s stationary at an employer’s worksite would need to be labeled with HazCom shipped container labels, but the same vehicle would be subject to DOT/PHMSA regulations while in transit. The 2016 joint memo allowed the same container to bear both kinds of labels and the final rule formalizes the allowance within the HazCom Standard.

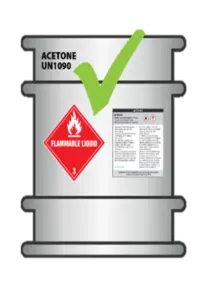

According to OSHA’s final rule, labels for bulk shipments may be:

- On the immediate container (as shown in the image above), or

- Transmitted with shipping papers, bills of lading (BoLs), or electronic means

Other Changes Due to HazCom Final Rule

Additional changes in the HazCom final rule include:

Responsibilities for Importers: The final rule canonizes guidance OSHA has provided over the years, most recently and most clearly in a 2018 letter of interpretation (LOI) responding to an inquiry submitted by VelocityEHS, that Section 1 of an SDS needs to have domestic/US contact and emergency contact information, so there can’t (for example) be a foreign emergency contact phone number in this section. If a US company is the first to import a chemical to the US and does not receive an OSHA-compliant SDS with domestic contact information, that company would become the responsible party and would need to author an SDS for the product containing domestic contact information in Section 1.

Classification methods: The final rule makes several revisions to classification methods, including:

- Adding new testing criteria in the form of UN Test O.3 for oxidizing solids;

- Aligning with Canada’s HPR by allowing chemical manufacturers to use the “exclamation mark” pictogram for Hazards Not Otherwise Classified (HNOC);

- Incorporating previous guidance on classifying Corrosive to the Respiratory Tract (CTRT) hazards into the text of HazCom and introducing new requirements for CTRT relative to Specific Target Organ Toxicity (STOT) and Skin Corrosion/Eye Damage;

- Skin Corrosion/Irritation: OSHA has aligned their skin corrosion/skin irritation tiered approach to classification to be in line with GHS Revision 8. Broadly speaking this elevates the importance and allowance of non-animal test methods, which can allow easier evaluation of chemicals under this hazard class.

- Slightly updating the numerical threshold for “In contact with water, emits flammable gases” – Category 3 materials;

- Modifying the flammable liquid definition to explain that the boiling point must be determined by the methods specified under OSHA’s Flammable Liquids standard (29 CFR 1910.106(a)(5)) and listed on the SDS; and

- Adding a conditional statement to the existing hazard statement for combustible dusts and an alternate hazard statement.

Hazard and precautionary statements

OSHA’s final rule makes several updates to HazCom regarding hazard and precautionary statements, including slight revisions to align with GHS Rev. 7. The final rule also adds a new paragraph, C.2.4.10, to address cases where substances or mixtures classified for multiple hazards may trigger multiple precautionary statements for medical responses and codifies an allowance of textual variations in P-statements originally provided in a LOI. OSHA intends for the latter change to improve alignment of HazCom with Canada’s HPR, which already allows minor differences in phrasing.

What is the Timeline for Compliance with OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule?

OSHA has extended the timeline for compliance with the final rule, compared to the timeline originally proposed in the NPRM. The proposed phased-in compliance timeline had been 1 year for manufacturers of substances and 2 years for manufacturers of mixtures, as measured from the final rule’s effective date of July 19, 2024. Between the effective date and the respective compliance dates for substances and mixtures, manufacturers of chemicals can comply with either the previous version of the HazCom Standard or the revised Standard when classifying their chemicals, authoring SDSs and labeling their shipped containers.

Based on stakeholder feedback, OSHA has lengthened the timeline in the final rule to 18 months for manufacturers of substances and 36 months for manufacturers of mixtures, as measured from the final rule’s effective date of July 19, 2024. Employers at workplaces using chemical products affected by the final rule would have six months from the manufacturer deadlines for substances and mixtures, respectively, to make any changes necessary to workplace hazard communication practices (e.g., workplace labels, written HazCom plan, and worker training) based on updated chemical hazard information provided by their suppliers.

The chart below summarizes compliance deadlines for different parties in the chemical supply chain affected by OSHA’s final rule:

| Affected Party | Requirement | Compliance Date |

| Manufacturers of substances | Classify chemicals according to revised criteria, including paragraph (d)(1) and new criteria for aerosols, chemicals under pressure, flammable gases and desensitized explosives, and update SDSs and shipped container labels as needed. | January 19, 2026 |

| Employers using substances affected by final rule | Confirm receipt of updated SDSs and shipped container labels from suppliers, and use information to update workplace labels, HazCom training and the written HazCom plan. | July 20, 2026 |

| Manufacturers of mixtures | Classify chemicals according to revised criteria, including paragraph (d)(1) and new criteria for aerosols, chemicals under pressure, flammable gases and desensitized explosives, and update SDSs and shipped container labels as needed. | July 19, 2027 |

| Employers using mixtures affected by the final rule | Confirm receipt of updated SDSs and shipped container labels from suppliers, and use information to update workplace labels, HazCom training and the written HazCom plan. | January 19, 2028 |

Note that in the above table, employers’ ability to use updated hazard information from their chemical suppliers to update their workplace HazCom practices depends on those suppliers meeting their respective deadlines for substances and mixtures.

What are the Main Takeaways about OSHA’s HazCom Final Rule?

The new HazCom final rule won’t have the same level of impact as the 2012 final rule that first aligned HazCom with the GHS. The current changes are more limited in scope, affecting a handful of chemical hazard classes, and specific details related to chemical classification and information on SDSs. Even so, many manufacturers will have to reclassify some of their products, resulting in new SDSs and shipped container labels. End users of those chemicals will need to know whether they have products affected by the changes, and be ready to track and use updated SDSs, including incorporation of any updated hazard classifications in their workplace labeling system and HazCom training.

The image below summarizes how the final rule affects different parties throughout the chemical supply chain. Keep in mind when looking at it that the first two categories, manufacturers and distributors, play dual roles as employers for their own workforce, and so would also need to meet employer obligations.

Preparation starts by having simple ways to maintain an up-to-date SDS library that you can access from anywhere. Make sure you have the tools you need to keep up with the changes that will now be going into effect and protect the safety of your workers.

Looking for More Information?

If you’re looking for more information to help you improve your HazCom practices, VelocityEHS has you covered.

Our written HazCom plan template will help you develop a written plan that meets OSHA’s expectations, with key prompts to consider aspects of HazCom affected by the final rule.

No matter where you are in the supply chain, our readiness checklist will help you identify areas to focus on to comply with updated HazCom requirements.

Finally, for an in-depth look at the final rule and the ways you can start preparing for compliance today, check out our upcoming live webinar.

Let VelocityEHS Help!

There’s never been a more urgent time to make sure your chemical and SDS management practices are working effectively. The VelocityEHS Safety Solution makes it easy for you to maintain an updated SDS library that you and your people can access from anywhere 24/7, along with streamlined ability to manage other core safety tasks such as inspections (including ability to develop and implement tailored chemical storage location inspection checklists), safety meetings, incident investigations, and corrective actions management.

If you need deeper insights into your chemical inventory, the Velocity Chemical Management Solution can help. You’ll get chemical ingredient indexing capabilities that use machine learning to extract information on chemical ingredients from SDSs, cross-reference them against various regulatory lists such as EPA’s Extremely Hazardous Substances (EHSs) and Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) reportable chemicals, and provide a Levels of Concern (LoC) summary containing regulatory radar screen “hits” and other key information, including established Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) you need to know when managing your indoor air sampling program.

Contact us today to learn more about our solutions and services and the ways we can help you maintain compliance with HazCom or schedule a demo.