By Phil Molé, MPH

It’s been a busy year for new regulations, so you might not have heard about MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule that lowers exposure limits to respirable silica for mine workers and establishes new requirements for mine operators to protect the safety of their employees. The requirements of the final rule will affect many US mine operators and companies that have mining divisions, so it’s important for those organizations to understand their compliance obligations.

In what follows, we’ll break down MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule and share some major takeaways to help mine operators prepare to meet the new requirements and, most importantly, to keep their workers safe from respirable crystalline silica exposure.

What is the Background of MSHA’s 2024 Respirable Crystalline Silica Final Rule?

Silica is a naturally occurring mineral found in the earth’s crust. There is a long history of humans mining silica to use in products such as glass, ceramics, bricks, and pottery, and consequently an equally long history of laborers having adverse health effects from working with silica.

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) notes that the material can cause lung and other diseases, like silicosis (a disease caused by inhalation of silica, characterized by inflammation and scarring in the form of nodular lesions), lung cancer, progressive massive fibrosis, chronic bronchitis and kidney disease. A mixture of respirable crystalline silica and coal mine dust can cause the infamous “black lung” disease, a condition resulting from long-term buildup of coal dust in the lungs, leading to inflammation of the walls of air sacs and eventually to fibrosis. The Associated Press (AP) reports that approximately one in five tenured miners in Central Appalachia has black lung disease, and the problem’s getting worse with dwindling mine capacity forcing miners to dig through more layers of rock to reach coal, generating more silica dust in the process.

Since the early 1970s, MSHA has maintained health standards to protect metal/nonmetal mine (MNM) workers and coal miners from harmful exposure to airborne contaminants, including respirable crystalline silica. MSHA had set the previous Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) of 100 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) based on the original American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) Threshold Limit Value (TLV) for silica, which was set in the late 1960’s.

OSHA also has a long history of addressing the hazards of occupational silica exposure. In 1974, OSHA’s sister organization National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) published a report titled “Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Crystalline Silica” that recommended moving away from using sand as an abrasive blasting agent to reduce worker exposures to respirable crystalline silica. In 1996, the Department of Labor (DOL) initiated a Special Emphasis Program intended to lower occupational exposure to crystalline silica and reduce the incidence of silicosis in the workplace.

In 2016, OSHA published two final rules for construction and general industry, to address common industry exposures from activities such as cutting and sawing of silica-containing materials.

The 2016 rules established a new exposure action level of 25 µg/m3 and reduced the PEL from 100 to 50 µg/m3 (both calculated as 8-hour Time-Weighted Averages, or TWAs). The standards also include requirements for installing exposure controls, implementing to monitor workers’ health and exposure to respirable crystalline silica (RCS), and maintaining a written exposure control plan. OSHA’s 2016 rulemakings also motivated stakeholders to place increasing pressure on MSHA to issue their own rulemaking to improve worker protections from respirable crystalline silica.

MSHA’s rulemaking process began in 2019 with the publication of a Request for Information (RFI) to solicit feedback from stakeholders on respirable silica to inform a rulemaking process. The RFI specifically asked for feedback on new or developing technologies and best practices to protect miners from exposure to quartz dust, the engineering controls, administrative controls, and personal protective equipment that can be used, and any other feasible dust-control methods to reduce miners’ exposures to respirable quartz. MSHA received a significant amount of stakeholder feedback on these questions.

After several years of compiling and analyzing feedback from the RFI, MSHA published the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) “Lowering Miners’ Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica and Improving Respiratory Protection” in the Federal Register in July 2023. There was a tremendous amount of interest in the NPRM, as evidenced by attendance at three public hearings organized by MSHA, which caused the agency to extend the public comment period. MSHA received 157 comments on the proposal and stated that they “carefully reviewed and considered the written comments on the proposed rule and the speakers’ testimonies from the hearings” during the process of developing the final rule.

What Does MSHA’s 2024 Respirable Crystalline Silica Final Rule Change?

The preceding discussion highlights that the final rule had been a long time coming, but it was finally published in the Federal Register on April 18, 2024. MSHA estimates that the provisions in their final rule will avoid 1,067 deaths and 3,746 silica-related illnesses.

Here are some of the most significant changes brought by MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule

Establishes a Reduced, Uniform PEL and AL

MSHA’s final rule reduces the PEL from 100 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) to 50 µg/m3 as measured as an 8-hour TWA. MSHA has also established an action level (AL) at half the PEL, or 25 ug/m3. Mine operators must conduct periodic sampling when miner exposures are at or above the AL but below the PEL.

Adoption of the reduced PEL and AL better aligns MSHA with OSHA, who as previously mentioned, established the same OELs for workers in general industry and construction via their 2016 final rules. Between 2016 and now, some companies have been in an awkward position, because (e.g.) they may have mining divisions covered by MSHA that extract raw materials including crystalline silica, and general industry facilities that process and distribute materials containing silica covered by OSHA, sometimes all on the same property. Technically, there was a gap in regulatory protections, in which a company could legally expose its mining sector workers to twice the concentration of silica as its general industry workers. In the 2016/2017 timeframe, VelocityEHS often gave presentations on the OSHA silica rules and advised attendees that if they had some workers subject to OSHA’s silica PEL and others to MSHA’s PEL, they should uniformly commit to keeping respirable silica exposures below the more protective OSHA PEL. Now that the MSHA final rule has aligned OELs for the mining industry with OSHA’s silica OELs for general industry and construction, there’s a much greater likelihood that all employees who work with silica will have the same exposure protections.

Requires Exposure Monitoring

Of course, setting OELS for respirable crystalline silica can only protect worker safety if employers are conducting to determine if their employees are exposed to air concentrations above the OELs. That’s why MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule requires mine operators to conduct air sampling to assess employee exposures to respirable crystalline silica.

The final rule also updates the standard for respirable crystalline silica sampling to ISO 7708: 1995(E), “Air quality— Particle size fraction definitions for health-related sampling.” MSHA adopted this standard by reference because it’s the international consensus standard defining sampling techniques for particle size fractions to be used in assessing potential health effects of airborne particle exposures on workers. Mine operators must conduct air sampling using respirable particle size-selective samplers that conform to ISO 7708:1995.

Mine operators should note that there are two very major differences between OSHA requirements regarding silica exposure monitoring and corresponding MSHA requirements, as follows:

PEL and TWA Calculation Method

There is a major variance between the ways employers can calculate TWA exposures between OSHA’s silica rules and the methodology allowed by the MSHA final rule. The differences center on how employers can sample exposures of employees who work longer than 8-hour shifts. MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule requires the employer to sample over the duration of the full work shift.

Suppose that a miner exposed to respirable crystalline silica works a 10-hour shift. MSHA dictates that an operator cannot just sample for 8 hours to confirm that exposures are under the PEL or AL as an 8-hr TWA, explicitly stating “under Part 60, the PEL and the AL apply to a miner’s full-shift exposure, calculated as an 8-hour TWA.” This means that the employer must collect the dust sample for the miner who works 10-hour shifts over the entire 10 hours.”

OSHA has no such “full shift” provision for determining TWA in their silica regs.

There’s No “Table 1” in the MSHA Final Rule

OSHA’s silica rule for the construction industry includes a Table 1 that lists certain activities and associated control measures. The OSHA rules provide an allowance stating if construction employers conduct Table 1 tasks exactly as described in Table 1, they would not need to conduct exposure assessments since the controls would result in negligible respirable dust generated. OSHA’s rules also allow employers in general industry to use Table 1 to reduce exposure monitoring obligations if they not only conduct Table 1 tasks as described in the table, with all associated controls, but also abide by other provisions of OSHA’s more stringent silica rule for construction, rather than the provisions within the general industry silica rule.

However, there is no Table 1 or any analogous table provided in MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule, which means that mine operators don’t have the available “outs” for exposure monitoring that employers in general industry and construction have.

MSHA had not specifically included provisions for a Table 1 in their NPRM, but the proposal sought comments on specific tasks and exposure control methods appropriate for a Table 1 approach for the mining industry that would adequately protect miners from risk of exposure to respirable crystalline silica.

Why didn’t MSHA adopt a variation of Table 1? According to the final rule, the stakeholder feedback MSHA received convinced the agency that a Table 1 approach would not provide the necessary protection for miners against overexposure to respirable crystalline silica under all mining conditions. MSHA also maintains that the changing nature of the mining environment necessitates exposure monitoring to ensure that controls are functioning effectively, properly maintained, and adjusted as needed to ensure compliance.

Requires Reporting and Corrective Actions for Overexposures

What if mine operators identify overexposures through their silica monitoring program? The MSHA final rule requires mine operators to take corrective actions needed to lower the concentrations of respirable crystalline silica to a level at or below the PEL. The operator must also conduct resampling to verify that control measures were effective at reducing concentrations and maintain records of all sampling conducted and corrective actions taken.

Many different regulations targeting harmful occupational exposures require employers to take corrective actions when sampling results indicate exposures above OELs. However, here’s where we encounter another major variance between OSHA and MSHA silica rules, this time concerning the obligation (or lack of one) to report measured employee exposures over the PEL.

OSHA’s silica rules don’t require employers to report exposures measured above the PEL to OSHA, but MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule requires such reporting to MSHA, stating that mine operators must “immediately report all exposures above the PEL to the District Manager or to any other MSHA office designated by the District Manager.”

The final rule states that MSHA adopted this overexposure reporting provision in response to stakeholder feedback about the importance of the agency’s active involvement in operator sampling and awareness of all overexposures so they’re better prepared to take appropriate actions, including compliance assistance and enforcement.

Specifies Methods for Controlling Silica Exposure

All mine operators must install, use, and maintain feasible engineering controls as the primary means of controlling respirable crystalline silica. Operators may use administrative controls, when necessary, as a supplementary control method.

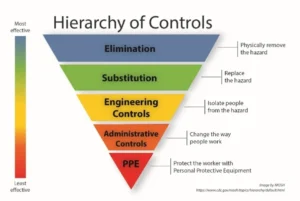

The key concept MSHA is using here is the hierarchy of controls, as shown in the image below.

Note that the hierarchy has the form of an inverted pyramid, showing the order that employers should use risk controls, with the most effective controls on top and the least effective on the bottom. It’s especially important to remember that the very bottom level is personal protective equipment (PPE), since there’s still a tendency for many employers to use PPE as a first line of defense rather than as a last resort, as intended. The levels of controls above PPE are more effective at reducing exposure, with the most effective being elimination/substitution since it eliminates exposure hazards at the source.

Of course, elimination or substitution is not often feasible in mines, where the nature of the work itself involves extracting minerals, so operators must use a combination of the next levels of controls. However, as you’ll soon see, MSHA is significantly limiting operator options to use PPE to reduce exposures.

Requires Temporary Use of Respirators at Concentrations Above PEL

What if sampling results identify areas where workers are exposed to concentrations of respirable crystalline silica above the PEL, but the mine operator still needs work to be conducted in that area before they can implement any controls?

MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule states that MNM operators must use respiratory protection as a temporary measure when miners must work in areas with concentrations of respirable crystalline silica above the PEL while the employer is developing and preparing to implement engineering control measures.

It’s important to understand the significance of this requirement and how it differs from OSHA’s silica rules. While both MSHA and OSHA stress the importance of the hierarchy of controls discussed above, OSHA allows respirators as a compliance method as a last resort if other and better control methods have not reduced exposures to levels below the PEL. OSHA’s silica rules also include provisions requiring employers to limit access to areas with exposures above the PEL to employees with respirators, and to make employees aware of the restriction.

On the other hand, MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule only allows respirator usage on a temporary basis while the employer is addressing reduction of exposures through other controls. That’s a MAJOR difference. This means, in practice, that once you identify exposures above the PEL in your mine workplace, you need to immediately start planning and implementing other controls to reduce exposure below the PEL. While it would not be surprising to see the mining industry collectively push back against this requirement, this is how the regulation is currently written, and operators need to start planning to comply with this provision.

Updates the Respiratory Protection Standard

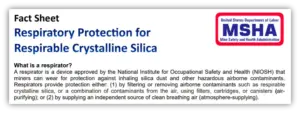

The final rule incorporates by reference ASTM F3387-19 (Standard Practice for Respiratory Protection). ASTM F3387-19 is the most recent respirator practices consensus standard and provides more comprehensive and detailed guidance than previous standards. MSHA also states that this update will improve worker protections by requiring more mine operators to provide miners with NIOSH-approved respiratory equipment that has been fitted, selected, maintained, and used in accordance with recent consensus standards. MSHA has published a fact sheet to provide additional guidance on respirator selection and use under the final rule.

What kinds of respirators can mine operators provide to their employees? According to the final rule, mine employers must provide either NIOSH-approved atmosphere-supplying respiratory protection or NIOSH approved air-purifying respiratory protection equipped with particulate protection classified as 100 series or High Efficiency ‘‘HE’’ under 42 CFR part 84. 100 and HE refer to the NIOSH-approved particulate filter classification and level of filtration (i.e., 99.97% filtration efficiency). Air-purifying respirators are more commonly used in the mining industry. Mine operators can also assign employees with atmosphere-supplying respirators (e.g., supplied air respirators), depending on the task and hazard.

Mine operators must also develop and maintain a written respiratory protection program to protect miners from airborne contaminants, including respirable crystalline silica, in accordance with ASTM requirements, and ensure that employees assigned respirators receive adequate training and use the respirators properly.

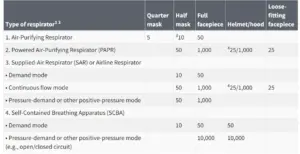

It should be noted that there is some variance between the respiratory standard adopted by MSHA and the respirator selection guidelines adopted by OSHA’s silica final rules. OSHA’s rules name OSHA’s Respiratory Protection standard in 1910.134 as the means for employers to select appropriate respirators. 1910.134 (d) covers respirator selection, and states that employers must use the assigned protection factors (APFs) listed in a table (see below) to select an appropriate respirator for the exposure conditions.

Most relevant to our discussion here, Section 1910.134(d)(3)(iv) further clarifies that for particulate matter exposures, employers must either provide an atmosphere-supplying respirator or an air-purifying respirator equipped with a filter certified by NIOSH under 30 CFR part 11 as a high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter, or an air-purifying respirator equipped with a filter certified for particulates by NIOSH under 42 CFR part 84.

While respirator selection criteria under OSHA and MSHA’s final rule have no direct conflict and generally lead to the same types of respirators being selected (namely, atmosphere-supplying or air-purifying), the selection process between the two regulatory frameworks does have slight differences. Mine operators not yet familiar with the provisions of ASTM F3387-19 should ensure they understand and follow the standard when selecting respirators for employees exposed to respirable crystalline silica. If a company has operating locations in both general industry and the mining sector, they should try to select and uniformly assign the respirators that provide the highest level of protection to all employees across both sectors.

Requires Medical Surveillance at MNM Mines

MNM mine operators must provide all miners with periodic medical examinations performed by a physician or other licensed health care professional (PLHCP) or specialist. These examinations must be available at no cost to the miner, which means that the employer must cover all associated costs, including costs of travel to and from the PLHCP, if applicable. The intent of this requirement is to enable MNM miners to monitor their health and detect early signs of respiratory illness from silica exposure.

There’s yet another variance from OSHA’s silica rules here. Unlike OSHA’s rules, MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule does not include a risk or exposure-based trigger for medical surveillance requirements, such as the provision in OSHA’s general industry silica rule that medical surveillance requirements only kick in when an employee has exposure to concentrations above the AL for 30 days in a year. MSHA states that they did not adopt an exposure trigger provision because they want to maintain consistency between the medical surveillance requirements for MNM and coal mines to ensure all miners have the information necessary for the early detection of silica-related disease.

The MSHA final rule also requires MNM mine operators to obtain a written medical opinion from a PLHCP or specialist regarding any recommended limitations on a miner’s use of respirators under § 60.15(e). The written medical opinion must contain the date of the medical examination, a statement that the examination has met the requirements of the section, and any recommended limitations on the miner’s use of respirators.

What happens if the PLHCP determines that a miner is unable to wear a respirator? The final rule states that the employer must provide that employee with a temporary job transfer to an area or to an occupation (within the same mine) where respirators are not required and provide the employee with compensation at least equal to the pay provided immediately prior to the transfer. Affected miners may only return to their initial work area or occupation when respirators are no longer required. Finally, the employer must maintain a copy of the PLHCP’s written determination must be maintained for the duration of the miner’s employment plus 6 months.

What is the Compliance Timeline for MSHA’s 2024 Respirable Crystalline Silica Final Rule?

The final rule is already in effect as of June 17, 2024, but on a phased-in compliance timeline. Coal mine operators must be in compliance with part 60 by 12 months after the publication date, while MNM operators must be in compliance by 24 months after the publication date.

The table below summarizes the compliance timeline for operators affected by MSHA’s 2024 respirable crystalline silica final rule.

| Type of Mine Operator | Compliance Date |

| Coal mine | April 18, 2025 |

| MNM | April 18, 2026 |

What are the Major Takeaways on MSHA’s 2024 Respirable Crystalline Silica Final Rule?

As you’ve learned, there are a lot of moving parts to MSHA’s respirable crystalline silica final rule. Here are some high-level takeaways to help you prepare.

You’ll now have an easier time providing the same level of protection for all employees in your company. Here’s the good news. In general, there is now a higher level of protection from silica exposures for mining workers because of the reduced PEL and AL, which are the same levels as OSHA’s PEL and AL for general industry and construction. If your company contains both general industry and mining divisions, that means you’ll have an easier time providing the same level of protection to all employees across your organization.

Even so, there are variances between OSHA and MSHA requirements. MSHA has updated the respiratory protection standard used as the basis for their respirator selection criteria. Unlike OSHA, MSHA hasn’t adopted a Table 1 listing the tasks and controls which would negate the need for exposure monitoring if conducted as described and does not allow respirator usage as a long-term solution to exposures above the PEL, which means mine operators would have to proactively use better control methods such as engineering controls or administrative controls to address overexposures. Not only that, but mine operators will need to report exposures above the PEL to MSHA.

You have little room for error. Collectively, these provisions mean you have little margin for error and inefficiency in your management of respirable crystalline silica. For example, you need to know if you have sampling results indicating exposures above the PEL quickly, so that you can report the overexposure to MSHA, and begin planning and implementing controls to reduce exposures below the PEL. That, in turn, means you need easy and effective ways to select to include in your sampling program, choose analytical laboratories, and easily access and share reports of sampling results. At the level of everyday safety, you also need to be able to create and deploy tailored inspection checklists to ensure, for example, that controls are in place and working effectively.

If you have worksites in the mining sector, now is the time to assess the tools you currently use for managing respirable crystalline silica exposure. You’ll need agile safety management tools to schedule and complete inspections, analyze results, and assign and manage corrective actions. Industrial hygiene ( can help streamline every aspect of your program management, from selection of SEGs to management of sampling results to tracking of respirator fit tests.

Let VelocityEHS Help!

To meet the deadlines of MSHA’s new respirable crystalline silica final rule, you need to start preparing now. Luckily, VelocityEHS can help you, because we designed our Industrial Hygiene software capabilities based on American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) best practices, and the input of busy EHS managers like you.

Our software helps you create and manage SEGs and embeds IH lab sampling and analysis guides directly into your system to help ensure you always sample using the right techniques. You’ll also be able to streamline your tracking of samples from collection to analysis with automated chain of custody forms, get guidance selecting analytical laboratories, and have the option to share sampling results with laboratory representatives or third-party consultants.

If you need the support of world-class safety software to help you better create, conduct, and manage inspections and all of your resulting corrective actions, we can help you there, too. Check out our case study to see how a large mining company successfully used our software to provide a single, centralized system for their safety management needs.

Contact us today to learn more about how we can help you improve your IH program and build safety and sustainability maturity.